As they say, oftentimes in life we don’t know what we’ve got until it’s gone. And only later, upon reflection, do we come to realize and appreciate what we had. Such is the case with my old friend Glen McIntosh.

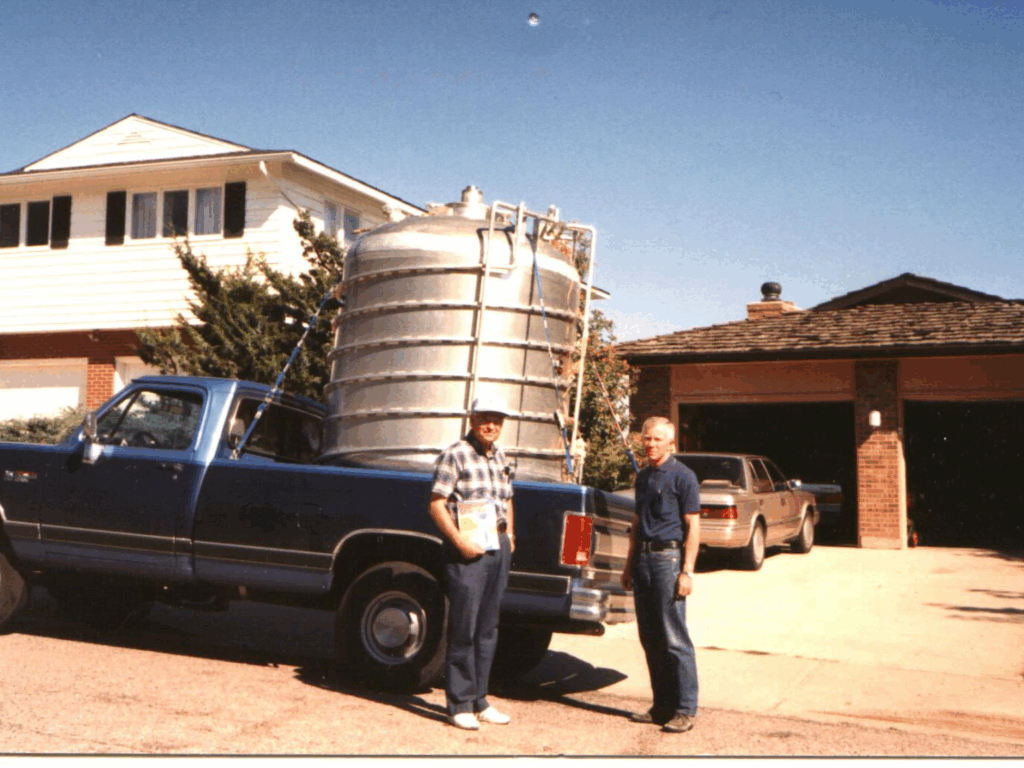

I first met Glen in about 1995, when applying for a mechanical engineering position at Cryogenic Technical Services (CTS), eventually being hired on in 1998. Thence began a series of exciting cryogenics projects, including: a cryostat for General Atomics, that was destined for the Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Lab, for fusion research, meant to hold a sample of deuterium or tritium at 7 K; a LOX subcooler for Boeing, supporting the fueling of the Space Shuttle; and a 19” warm bore cryostat for detecting Anti Matter for Harvard University, destined for CERN.

Working alongside Glen was like drinking from a fire hose. He was a hard fellow to keep up with.

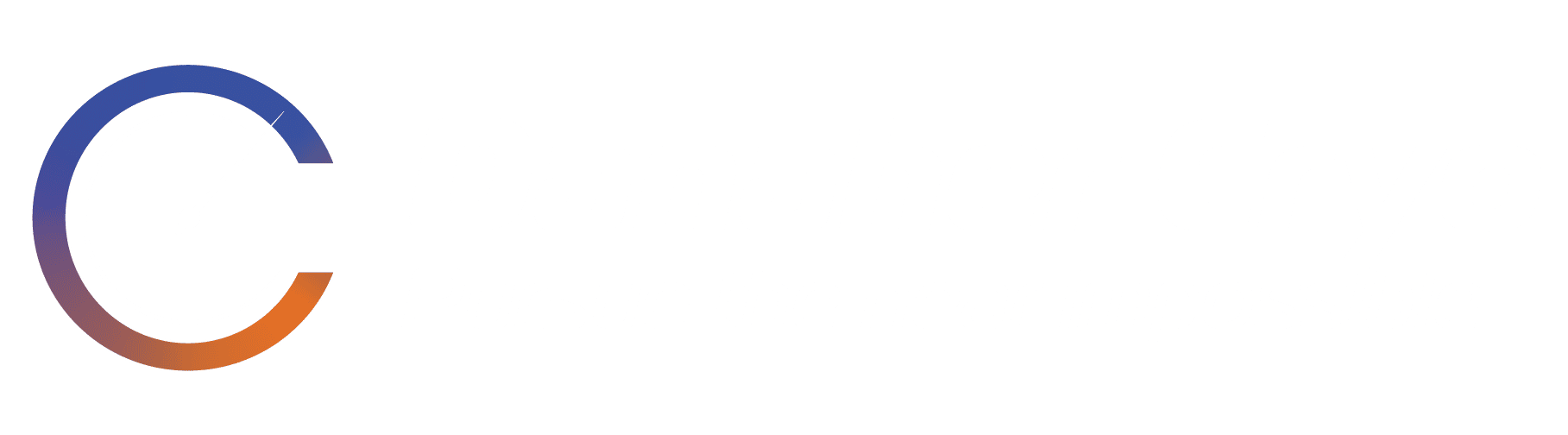

When it came to cryogenic projects, anyone who knew Glen would agree with me that there was no job too unusual or intimidating for him to take on. One such project was a liquid helium storage dewar for an around-the-world balloon mission. Earthwinds hired CTS to design the 750-gallon dewar that would supply helium gas to the balloon for this audacious mission. After the dewar was fabricated at CDM in Denver, Glen and his son Ross drove the dewar out to NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, MD for testing that would simulate flight at 35,000 feet. The balloon made the cover of the October 1990 issue of Popular Science Magazine. Unfortunately, the multiple attempts to circle the earth were not successful due to weather conditions.

But in addition to cryogenics, for me, the more rewarding part of knowing Glen (not to diminish one bit what was to be learned from him about cryogenics), was the stories he shared about times gone by. Being 37 years my senior, and having lost my dad at age nine, Glen became somewhat of a father figure to me. And I very much relished hearing him recount the “old days.” Heck, I didn’t even mind hearing them repeated. Perhaps doing so would help them sink in. And, in some cosmic sense, prepare me for this honored exercise.

It was a somewhat dangerous habit to stop by his office at the end of the workday and say goodnight. For he was known to lure you into the telling of one of his marvelous recountings. And I’m thoroughly blessed to have benefited from many.

Please be patient as I reminisce on a few such vivid tales.

If I go in chronological order, the first episode would have to be when, in about 1929, Glen was about three years old, he was visiting his Granddad Thol Wolfe at the Wolfe farm just north of Conway Spring, KS. As the story goes, Granddad and Glen were riding in Thol’s blue Whippet when they heard a rolling thunder. (Whippets were only manufactured from 1927 until 1931.) They pulled over and watched as a 1,000 (that’s correct, one thousand) airplanes flew overhead in formation.

It was the Army Air Corps, putting on their show-of-force flight across the country.

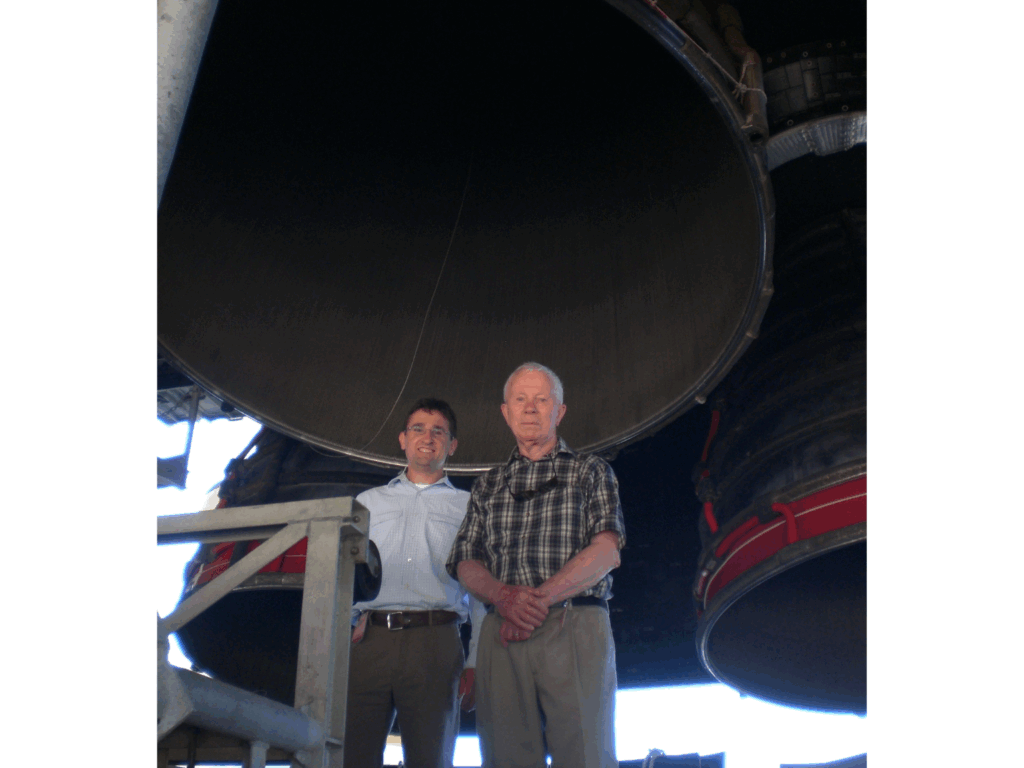

Perhaps it was those airplanes passing overhead that gave Glen the flying bug. For following high school he was selected for the Navy Aviation program. During his Navy time, Glen was stationed in both Iowa City and Ottumwa, Iowa, and Corpus Christi, Texas. Glen tells how he and his buddies would swoop down and touch their tires on the Mississippi River. I bet you couldn’t get away with doing that today.

Not long ago, I was telling Glen about a windmill that I recently put up on our property and that spurred him to tell yet another flying story. This one was set near King Ranch in Southern Texas, while he was stationed in Corpus Christi. Glen tells of him and his buddy flying just 50 or 60 feet off the ground, weaving through the trees chasing each other. Upon rounding a particular grove, he found himself flying directly at a man atop a drilling rig. He and the worker were at the same elevation, looking straight at each other, with Glen quickly closing in. Glen (and his buddy right behind) made a quick maneuver to avoid the rig, and proceeded on their way. I think Glen wondered long after the incident what that oil worker made of that experience.

From hearing the stories, it was obvious that Glen had a love for flying. Accordingly, I think he had a sense of disappointment that his instruction program had to come to an end. He tells the story about one of his last flights. Before he gave up flying, he wanted to fly 200 knots. His Douglas SBD dive bomber wouldn’t cruise at that speed, but it could go that fast if you pointed it downward. So, he proceeded to do just that, and upon reaching the desired speed, he slowly pulled out of the dive and flew back to the airport. And as he was walking away from his airplane, his mechanic mentioned to him that he was dragging his antenna. As I recall, he played a little dumb, and shrugged at that report, as though he had no idea why that might be.

Even though Glen’s completion of the Navy Pilot program was in November 1945, he would tell you this story like it was yesterday. He finished in Chicago and, before he boarded the train to head back to Martin, SD, he went into Chicago and bought his dad a box of cigars.

Glen made no secret of his being adopted. He would even recall how, when he was just a small boy, at the Wolfe farm in Kansas, his granddad would tell Glen that “your parents wanted you.”

My last fond memory took place on February 12, 2025, just six days before his passing. Glen’s son Ross informed me that Glen seemed to be slowing down and invited me over to visit. I took him up on the offer right quick like, and, as I entered his home, he ordered Ross to get the red wine out of the fridge, so that he and I could together have a drink. And sure enough, we did. I offered up a toast to “99 years.”

And, as per usual, he then proceeded to tell stories.